I want to add a few quick follow-up thoughts on yesterday’s topic: The large differences across four national surveys in the number who offered an opinion on whether Samuel Alito should be confirmed as a Supreme Court justice. What should we make of the roughly 50% of Americans who will offer an opinion on Alito’s confirmation when pushed by an interviewer but not when offered the option “or can’t you say?” Survey researchers have long debated this issue, and the answer is not as easy or obvious as it may appear.

One theory says that those “pushable” respondents have no real opinion or attitude on the Alito nomination but just make an answer up on the spot under the pressure of the interview. Taken to an extreme, this theory would have respondents just making up meaningless answers at random. Under this first theory, we would probably want to ignore these “pushed” attitudes.

Another, and somewhat more enlightened theory argues that some respondents opt for “I can’t say” when offered because they would rather not expend the mental energy necessary to answer the question. To put it in academic terms, they “satisifice” and take the easy way out rather than expending the “cognitive effort” necessary. So some of those 50% may have a real attitude about Alito in there somwhere, and the gentle push from the question format or interviewer forces them to think it through.

Even when respondents form opinions and make them up on the spot, their answers are often drawn from real attitudes. Thus, when pushed, respondents will use what information and cues the question provides to work their way to an answer. For example, if you know only that Alito was nominated by President Bush, and you have strong feelings one way or another about President Bush, you may base your answer on those attitudes.

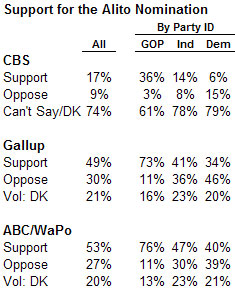

With that in mind, consider the results to the question of whether Alito should be confirmed when tabulated by party in the table below:

Notice that among Republicans most of the difference between the CBS poll (which offered an explicit “can’t say” option) and the Gallup and ABC/Washington Post polls (which did not) is in the support category. When pushed, Republicans are supportive by a roughly four-to-one margin. But independents and Democrats appear to divide about evenly when pushed. About half support and about half oppose.

So this example does not settle the debate. When pushed, Republicans appear to draw on their partisanship in forming (or deepening) an opinion on whether Alito should be confirmed. But it is not at all clear what independents and Democrats are doing when pushed. Are they drawing on other attitudes? Are some basing their answer on partisanship while others are just “acquiescing” (see satisficing under the “cognitive psychology” section). Are they just mentally flipping coins? It’s hard to say.

Either way, again, the lesson for poll consumers is to watch out when we ask about issues or people that the public are not following closely. The safest conclusion is that when offering an explicit “don’t know” option boosts that that category by 50 percentage points, the opinions offered by those pushed to an answer are very soft.

Source links: CBS News poll, Gallup poll, ABC/Washington Post Poll

Or are their two factors at play. Given the republican split on Miers, there seems to be more than just a “Bush proposed, so I support” attitude in the GOP. There will undoubtedly be those on both sides that will look at this solely in the prism of Bush for their support or objection. But like the Miers split, their will be those who will have at least a passing, if not in depth, knowledge of the candidate (or what is being said about the candidate). So perhaps the democratic split is like the GOP Miers split. Between those who would oppose anyone proposed by Bush and those who think the little they know about Alito says he is competent.

Yes, and beyond the question of offering uninformed opinion, there’s the further question of what “informed opinion” is. Could any of the respondents explain Alito’s view on stare decisis (or even explain what stare decisis is). You might ask a thousand people whether they believe string theory is sound science, but I don’t know that the question would be much decided by the results.

Jeff,

You are correct, and yet there is a huge difference between polling on string theory and supreme court nominees. String theory will be true or not independant of any poll. Politics is arguably moved by a poll and to some degree can be measured by a poll. So while many of the pro or con opinions in a poll may be uninformed, that won’t stop the person polled from voting. When the left puts a full court press on a nominee and then comes up short in public opinion (and senate action to stop), that is noted in politics. Few things are more deadly in politics than to be made to look foolish or incompetent. I think the poll numbers, while certainly not an indication of voters knowledge of the minutia of judicial proceedings, is an indication that what the left is so up in arms about is not what the majority of voters is concerned with.

This may help explain why the democrats have only mustered one presidential election majority in the last 40 years (50.08% in 1976).