Virtually all of the national surveys use some form of cut-off procedure to define likely voters. Respondents are either classified as likely or unlikely voters. There is one notable exception: The CBS/New York Times poll, whose likely voter model involves weighting respondents by their probability of voting.

Warren Mitofsky, then CBS polling director (now director of the network exit polls) developed the CBS/NYT model using validation studies conducted by the University of Michigan’s National Election Studies (NES). The NES regularly checked registration records to see if respondents had actually voted. Mitosfky used questions identical to those on the NES to ask about registration, intent to vote, history of past voting, and when they moved to their current address. All of these questions had been shown to correlate with actual turnout. Mitofsky used the survey results to classify voters into several groups, ranging from low to high turnout, and weight by the probability of voting derived from the NES studies (CBS has posted a more detailed description of the current procedure here).

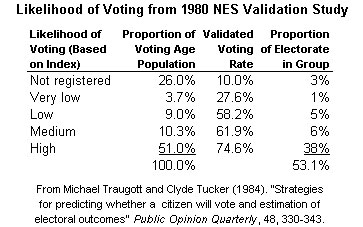

While CBS does not release its actual probability data, a 1984 article in Public Opinion Quartely authored by Political Scientists Michael Traugott and Clyde Tucker (then an assistant survey director at CBS) included similar data that helps show how the model works. The table below shows data from the 1980 NES. Those who said they were not registered to vote are in the first row, followed by four groups of voters ranked on their reports of past voting and interest in the campaign:

The middle column shows the percentage of each group of respondents that actually voted in the 1980 election for President. The CBS procedure is to weigh non-registrants to a probability of zero, then weight each group of registered voters by its probability of voting (the percentage that actually voted). Thus, using the Traugott/Tucker data as a hypothetical example, they would multiply each respondent in the “high” turnout group by a “weight” of 0.746, respondents in the medium group by 0.619 and so on. Since 2000, CBS also started giving a weight of 1.000 to any respondent who says in the survey that they have already voted absentee.

The main advantage of the CBS model is that it uses the entire sample of registered voters, unlike the cut-off models that throw out respondents not classified as likely voters.

The main disadvantage is that it relies on data from validation studies. The model is only as good as the probabilities it applies and cannot be applied in statewide races where such data is unavailable. Also, the National Election Studies stopped conducting validation studies in the late 1980s. As a result, CBS did their own validation study following the 2000 elections. They called back respondents to pre-election surveys in November 2000 “to ask whether they actually voted to refine what by then were outdated probabilities.” Since the 2000 study depended on self-reports of voting behavior, CBS adjusted the probabilities to account for the usual over-reporting.

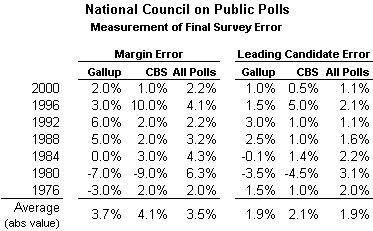

Does the CBS model forecast elections more accurately than the Gallup model? Perhaps not, although both have performed similarly in presidential elections. According to the error rates calculated by the National Council on Public Polls, the final presidential election polls conducted by CBS produced slightly more error than Gallup on the margin between candidates since 1976 (4.1% vs. 3.7%) and error for the leading candidate (2.1% vs. 1.9%; error calculations explained here). The differences appear to be random: CBS did slightly better three times (especially 1992), Gallup did better four times (especially 1996). It is also worth noting that CBS had the second lowest rates of error of all polls in the 2000 elections, showing Al Gore one point ahead of George Bush (45% to 44%) on their last poll.

One big apparent advantage of the CBS method is that it has shown more stable results among likely voters over the course of the fall campaign without weighting by party. In October of 2000, while the Gallup poll swung wildly, showing Bush variously leading by as much as 13% and trailing by as much as 11%, four of the five CBS surveys showed the race even or Bush leading by a single percentage point. The widest lead CBS gave George Bush was 4% (46% to 42%) on their next to last survey. This year, the CBS has been similarly consistent: The three surveys of likely voters conducted by CBS in October have shown Bush ahead among likely voters by between one to three percentage points.

I have always been a fan of the CBS model, if only because it provides such an elegant solution to the likely voter problem. When it comes to turnout, the best a poll can do is tell us the relative probabilities of different kinds of voters. Some kinds of people tend to vote more often, some less. If we must try to forecast the probable electorate, why throw out respondents if we don’t have to? If standard “cut-off” models produce more volatile results, the answer seems even more obvious.

Note: I have certainly not attempted a thorough search, the only application of probability weighting at the State level I am aware of is the Minnesota Poll conducted by Rob Daves at the Minnesota Star Tribune.

According to Slate, the LA Times also weights responses by the voter’s likelihood of voting. See http://slate.com/id/2108778/. I am unable to verify this on the LA Times website.

Here’s a softball from tinfoil-hat territory: is it possible that Gallup’s much-disputed LV model takes into account the fact that certain demographic groups seem to have a harder time getting their votes counted? You know, the most error-prone ballot machines tend to appear in certain precincts, or staff shortages at voting locations, affecting primarily X-constituency, etc.

With all the stories currently out concerning “dirty tricks” voter suppression tactics here and there, it’s an interesting idea that maybe, in weighing voter intentions vs ability to be counted, Gallup might be the one who gets this election right.

Okay, sorry about that. Back to the science.

While I agree with you that the CBS method seems more elegant, I find their probabilities rather disappointing. A huge jump from “Very Low” to “Low”, a trivial jump from “Low” to “Medium”, and a medium ranger jump from “Medium” to “High” just doesn’t seem right.

And the fact that they expect 1/4 of their “Highly likely voters” not to vote makes me think their sorting just isn’t that good.

“Note: I have certainly not attempted a thorough search, the only application of probability weighting at the State level I am aware of is the Minnesota Poll conducted by Rob Daves at the Minnesota Star Tribune. ”

And we know how well that has worked.

Like you, I do have an affinity for the CBS methodology. Earlier this year I was asked which polls on the national level I prefer, and after trying to dodge the question by saying (truthfully) that all of them give me some info, I said I like Battleground among those who weight to party, and CBS among those who dont, with Fox also up there.

The polls are off Kerry will win by 3-5% on election day and by 60+ points in the EC. The simple reason is that the polls have not fully taken into account the record number of Democrats that will vote on Tuesday to remove the hated Bush.

Every poll takes a sample of registered and or likely voters based on each parties registration and prior voting patterns in past elections in that state or throughout the USA. These samples are based on PROJECTED voter turnout and there is no way any poll can project the large increase in % of Dems voting in 04 compared to 2000.

Every close swing state will go to Kerry and it will all be over on election night.

Another Day, Two New Polls

The morning brings two new surveys: One from CBS and the New York Times (article, results, CBS analysis, results on Iraq/terror, elections) and one from Bloomberg and the LA Times (article, results). Both surveys are lengthy and the accompanying analys…