Several readers have asked for my opinion on the so-called “generic vote” or “generic ballot” asked on national surveys to gauge Congressional vote preference. Given the obvious inability to tailor a national question to match 435 individual House races, this question asks about party rather than candidate names: “If the 2006 election for U.S. House of Representatives were being held today, would you vote for the Republican candidate or the Democratic candidate in your district?” Although most national surveys currently show a statistically significant Democratic lead on this question (see the summaries by RealClearPolitics or the Polling Report) many analysts have questioned the predictive accuracy of these reports, particularly this far out from the election.

I raise this topic today because of a new batch of surveys from Democracy Corps that show how the generic vote compares to other measures of candidate preference in parallel surveys conducted in three congressional districts. To be totally honest, I am skeptical about the utility of the generic ballot question but have never formed a strong opinion on this controversy, largely because I ask the generic question so rarely on internal campaign studies. I want to direct readers to the Democracy Corps surveys because they provide some examples consistent with my own experience that help explain my own skepticism.

How accurate is the “generic ballot” for Congressional vote preference? An analysis by the Pew Research Center in October 2002 concluded in off-year elections, the final pre-election measure of the generic vote (presumably as reported among “likely voters”) has been “an accurate predictor of the partisan distribution of the national vote,” showing an average error between 1954 and 1998 of only 1.1%. Similarly but less formally, MyDD’s Chris Bowers did a simple comparison last year and found that on average these results for the final polls in 2002 and 2004 came reasonably close to the final margins.

However, these final surveys are obviously taken very late in the campaign and typcially among likely voters. The surveys we are seeing now typically report results among registered voters, a distinction that according to various reports by the Gallup organization consistently tips the scale in favor of the Democrats. For example, a recent (subscribers-only) analysis reports that “Democrats almost always lead on the generic ballot among registered voters, even in elections in which Republicans eventually win a majority of the overall vote for the House of Representatives.”

In another report released in February, Gallup’s David Moore put it more plainly: “Our experience over the past two mid-term elections, in 1998 and 2002, suggests that the [registered voter] numbers tend to overstate the Democratic margin by about ten and a half percentage points.” Similarly, taking a somewhat longer view (“most of the last decade”) Gallup’s Lydia Saad reported last September that “the norm” a five point Republican deficit among all registered voters that “converts to a slight lead among likely voters.” Make “some adjustments” to the generic vote, she wrote, and one can “make a fairly accurate guess about how many seats each party would win.”

Not everyone agrees. For example, in a recent column entitled “Don’t Bet on the Generic Vote,” Jay Cost argued that the problem is less about a “consistent Democrat skew,” than about the weak predictive value of the question this far out from an election.

This debate will obviously continue, and while I am now paying closer attention to it, I have not done so over the years. As an internal campaign pollster, I have helped conduct hundreds of surveys for candidates for Congress that almost never included the “generic ballot.” We focus instead on questions that provide the candidate’s names. We have included the generic ballot question in a few rare instances, and the results have been very different from questions that include names and often quite puzzling. The experience left me and my colleagues feeling skeptical about what the generic ballot measures.

Now comes a unique release of data from Democracy Corps — a joint project of Democratic consultants Stan Greenberg, James Carville and Bob Shrum — that allows for a comparison of the generic ballot to more direct measurements of vote preference within three individual districts. In fact, the latest Democracy Corps release provides ordinary political junkies with a great window into the surveys that internal campaign pollsters like me typically conduct for our clients.

Having said this, I should note that in highlighting this release, I am breaking a longstanding rule I set for this blog of refraining from “comment on any race in which we are also polling.” So in the interests of full disclosure: Joe Sestak, the Democratic candidate in Pennsylvania’s 7th CD is a client of my firm, although I am not working on his race personally. I have chosen to break my usual rule largely because the three surveys help demonstrate two things of interest to MP readers: (1) the questions that internal campaign pollsters use to assess where a race stands and (2) a close-up view of the generic vote and what it may and may not measure. I will not comment here about the implications of the results of these surveys for any of the candidates involved, except to reiterate the advice offered before that conumsers should always read partisan polls with larger than usual grain of salt.

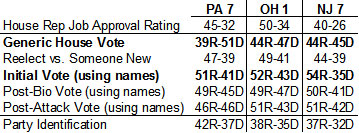

Back to the Democracy Corps survey. The three districts polled involve Republican incumbents that independent analysts rated, according to Democracy Corps, as falling in “middle or lowest tier in their assessments of the 50-60 races in play this election cycle.” The questionnaire includes:

- A job approval question about the incumbent (Q11)

- A generic ballot Congressional question without candidates names (Q30)

- The so-called re-elect referendum question that includes the name of the incumbent, but not the challenger (Q32)

- A ballot question that includes the names of both candidates (Q33)

- An”informed” question following brief positive descriptions of both candidates in each race (Q40, Q42 & Q44)

- An “informed” question following an exchange of potential negative attacks by the two candidates (Q46)

Campaign pollsters typically use both reelect referenda and informed vote questions to try to get past the tendency of well known incumbents to lead relatively unknown challengers in early horserace questions involving candidate names. Campaign pollsters typically find they get a better read on the way a race will ultimately play out with balanced “informed” questions using the same basic format as those in the Democracy Corps surveys.

Now, check the table of results above and note the difference between the generic ballot test in each district and any of the vote questions involving candidate names that follow. The results of the generic preference question in each district are very different from those based on the names of the candidates, including both the current snapshot and on informed questions that attempt to simulate the exchange of information that would occur in a campaign. Specifically, note how much lower the generic preference for the Republican candidate is in each district compred to the Republican’s peformance on the “named” preference questions that follow later in the survey.

My conclusion: I am not sure what the generic vote is measuring right now, but it clearly measures something different than current candidate preference and something different again from the informed questions that try to preduct how voters will respond as they learn more about the candidates.

This is not to say that the generic vote is useless. As we get closer and closer to the election, pre-election polls will do an increasingly better job projecting the likely electorate. Moreover, voters will get increasingly better acquainted with candidates and start to make form more lasting preferences. Thus, my hunch is that as we get closer to November, the generic vote will gradually becomes a better measure of actual vote preference.

Right now, however, the value of the generic vote is mostly for comparisons with polls conducted by the same organzation using identical language at this point in prior election cycles. For example, the Pew Center did just that and concluded, “there has been only a handful of occasions since 1994 when either party has held such a sizable advantage in the congressional horse race.”

But remember the limitations: These generic questions may be telling us more about voters’ general attitudes about politics right now than about their candidate preference. And, as with any poll, tomorrow’s opinions may be different.

Thanks for doing such great work on this blog!

Could this also relate to higher rates of ballot spoilage in poorer counties, and thus less votes for Democrats than expected on average?

Polls That Matter And Polls That Don’t

This article about Democratic poll numbers is producing a lot of buzz: “Republicans are in jeopardy of losing their grip…