It gets more interesting. Here is the promised update to the posts of the last two days, based on some fascinating analysis sent by Jason Dempsey, an Army Infantry officer and Columbia PhD candidate currently completing a teaching tour at West Point. As part of his doctoral dissertation, Dempsey conducted a true random sample survey of the U.S. Army population in 2004. The results show that Peggy Noonan’s comment that in her experience, “career military men” are rarely “social conservatives” reflects the reality of the Army population in some ways but not in others.

Dempsey’s data confirm the findings I discussed yesterday showing that Army officers are far more conservative than the U.S. population, both in terms of their ideological self placement and their stands on specific “social” issues. If by “career military” Noonan meant officers, then as Dempsey puts it, “that population is probably more socially conservative than she has experienced.”

On the other hand, Dempsey finds that Army enlisted personnel, including those he classifies as “careerists,” have attitudes on political issues that largely resemble those of the larger U.S. population. He also makes an important observation about the demographics of the enlisted Army personnel:

Enlisted soldiers also tend to be younger, much more diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, and come from more modest socioeconomic backgrounds than officers. This correlates with more moderate or apolitical stances on larger political/social issues and less engagement in the political process.

So in that sense, Noonan has a point.

Dempsey drafted some analysis exclusively for MP readers that I have posted in full on the jump. I have also created a PDF of his analysis suitable for printing. Either way, it is well worth reading in full. Thank you, Major Dempsey, for sharing it.

PS: See also this recent New Yorker “Talk of the Town” item on Dempsey and filmmaker Eugene Jarecki.

PPS: A tip of the hat to GWU Professor John Sides, who originally alterted me to Dempsey’s research.

Jason Dempsey’s analysis:

Mark,

Having studied the social and political inclinations of members of the United States Army for some time I’m happy to comment on your reader’s question.

First, you fairly accurately summed up the state of polls on the social and political attitudes of active members of the armed forces-they are few and far between. One you didn’t mention was the study conducted by the Triangle Institute for Security Studies (TISS) in the late 1990’s (http://www.poli.duke.edu/civmil/). The TISS project was unique in that it got access to military schools and did some fairly extensive surveys of select groups of up-and-coming senior leaders. It is worth looking at for an overview of the attitudes of higher-ranking officers across the various services.

In 2004 I was able to conduct a true random sample mail survey of the Army population focused primarily on the question of Hispanic integration that included questions on civic engagement, socialization, and attitudes towards social and political issues. Everyone in the Army was eligible to be included in the survey with the exception of three groups 1) Generals and Command Sergeants Major (there are too few to guarantee confidentiality); 2) Privates (PV1 & PV2), who are notoriously hard to reach as they are predominantly still within their first year of service and are either in some form of training, moving between training, or moving to their first unit; and 3) those soldiers who were currently in a combat zone. Due to the high turnover of the previous year excluding group three did not prevent us from surveying recent combat veterans. Fully 376 of our 1189 respondents, or 32% of our sample, were veterans of either Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003-2004) or Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan (2001-2004); and 143 indicated that they had been involved in direct ground combat in the previous two years. Overall, the response rate for the survey was 45%. All reported data is weighted to reflect the composition of the Army (minus excluded ranks) as of February 2004, when the sample was drawn. Now, with the methodological disclaimers out of the way, on to your question…

First, I think that Noonan’s comment may have drawn more interest than usual because it is counterintuitive. We tend to think of the military as an inherently ‘conservative’ institution. And what is fascinating about her quote is that the way she describes the ‘career military man’s’ approach to such questions used to fit the definition of conservatism (an outlook that shunned government activism and approached such issues as “private and not subject to the movement of machines”).

Indeed, Morris Janowitz (the father of military sociology) and Samuel Huntington (the father of civil-military relations theory) both described the conservative ethic, as practiced by the military in the 1950s and 1960s, as a distinctly nonpartisan means of political expression (See Janowitz, 1960/1971 p. 236, and Huntington, 1957). That definition of conservatism clearly no longer holds so we just need to make sure that we are all comparing apples to apples in our approach.

In the Citizenship & Service survey the question I asked about conservative-liberal self-placement was worded, “In terms of politics and political beliefs, where would you place yourself?” Respondents then had the option of placing themselves on the standard 7-point ‘extremely liberal’ to ‘extremely conservative’ scale.

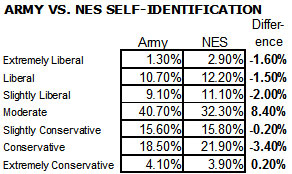

On the whole, the Army looks remarkably like the civilian population on this question, as represented by the 2004 NES dataset (Note that this data is not directly comparable. NES offered a “or have you not thought much about this” option that a large number of respondents chose. The Army survey did not offer this option, and it might be assumed that a large number of the NES respondents who said they hadn’t thought much about the issue-had they been not given this option– would have chosen the moderate category):

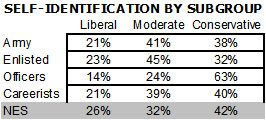

However, the story gets a lot more complicated when you start breaking the Army up into key subgroups. Among officers a clear majority, 63%, self-identify on the conservative end of the spectrum compared to only 32% of the enlisted ranks. (The overall numbers look the way they do because officers only make up about 14% of the Army). This leads to the second question about Noonan’s statement: does she consider a ‘career military man’ to be an officer, or anyone who commits to 20 years or more of uniformed service?

Leaving open all possibilities, I present the following in terms of the entire Army, officers, enlisted, and ‘careerists’ (defined as anyone who has spent 15 or more years in the Army OR states that they will ‘definitely’ or ‘probably’ stay in the Army until retirement). In the interest of brevity, I will leave out any discussion of differences among gender, racial and ethnic groups, but suffice to say that many of the same trends that one sees in the civilian population apply to the Army as well.

Among ‘careerists’, 21% self-identify as liberal while 40% identify as conservative. This follows from a generally older and more established cohort (again pointing to the difficulty of broadly defining ‘conservatism’).

As for Noonan’s point, it would seem the Army data supports her anecdotal evidence, unless she was specifically referring to officers.

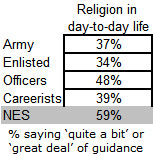

When it comes to the importance of religion in daily life, the Army data follows a similar pattern, with officers the most likely to say that religion provides ‘quite a bit’ or a ‘great deal’ of guidance. Overall people in the Army are significantly less likely than civilians to state that religion provides ‘Quite a bit’ or a ‘Great deal’ of guidance in day-to-day living. HOWEVER, the Army question is not directly comparable to the NES question because the NES question did not explicitly offer a ‘not religious’ or ‘no guidance’ option.

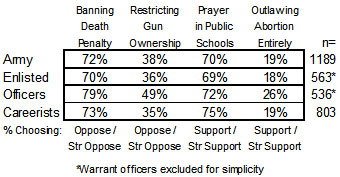

On a few ‘hot-button’ social issues I offer the following summary stats. I don’t have good comparisons with the civilian population handy at the moment, but the questions were worded as follows:

“Please indicate your position on the following domestic issues:

a. Banning the death penalty

c. Allowing prayer in public schools

d. Placing more restrictions on gun ownership

e. Outlawing abortion entirely”Respondents were then given five options, Strongly Favor, Favor, Strongly Oppose, Oppose, and Don’t Know/No Opinion.

Making rough comparisons from what we know historically from surveys of the general public, soldiers don’t appear to differ much on these issues (for example see Ben Page and Bob Shapiro’s, The Rational Public for an overview).

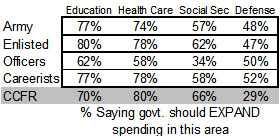

We do, however, have some comparable civilian data from the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations (CCFR) 2004 survey on preferences towards government spending on various social programs. On these issues the Army is largely comparable to the civilian population, with officers again being the exception.

Overall, the Army tends to track civilian attitudes and ideological self-placement. Untold in this brief overview, however, are underlying stories of demographics in the Army. The enlisted ranks drive overall attitudes due to their numbers relative to the officer corps. Enlisted soldiers also tend to be younger, much more diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, and come from more modest socioeconomic backgrounds than officers. This correlates with more moderate or apolitical stances on larger political/social issues and less engagement in the political process.

However, I’d say that if by ‘career military men’ Noonan is referring to officers, then that population is probably more socially conservative than she has experienced. At least by reported role of religion and ideological self-placement, the Army officer corps appears to exceed the rest of the Army and the civilian population in its ‘conservatism’. This would make sense as the Army officer corps, and particularly its senior ranks, is predominantly white and male and comes from a middle- to upper-middle-class background (officers are required to have a Bachelor’s degree before commissioning). Officers also deviate from the rest of the Army in terms of attitudes towards hot-button social issues, and they do appear more frugal when it comes to spending on programs related to social welfare (although some of this may be due to the Army’s retirement package, which might reduce an officer’s concern over the state of health care or Social Security). A tighter definition of ‘social conservatism’ and more detailed multivariate analysis (as well as tests of statistical significance) are therefore clearly needed to take this question any further.

Anyway, hope this sheds some light on an otherwise under-studied area.

Anyone interested in more nuanced analyses of these and related questions is welcome to a paper presentation I will give at the American Political Science Association convention on September 1st. Our paper on Army racial and ethnic attitudes, as they relate to Hispanic integration (co-authored with Bob Shapiro) should also be coming out in an edited volume from the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute this fall. Additionally, we have several papers in the works on voting and partisanship (co-authored with Craig Cummings and Mat Krogulecki) that should get out this fall and winter.

Initial funding and support for this project was provided by the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute through the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy at Columbia University. Additional funding was provided by the Academic Research Division of the United States Military Academy, the Saltzman Institute for War and Peace Studies and a fellowship grant from the Eisenhower Foundation.

Jason Dempsey is an Army Infantry officer currently completing a teaching tour at West Point. This research is part of his doctoral dissertation in political science at Columbia University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Military Academy, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense or U.S. Government.

This is a fascinating topic and deserves all the detailed examination it can get. The issue can be approached in two ways…

1) To what extent is the military in general, and the officer corps in particular, unrepresentative of the population at large? A permanent ideological and sociological disconnect between the republic and its military would pose perils for both. To civilians, the military could come to seem like a Praetorian Guard. The military, in turn, could come to feel misunderstood and disrespected in its dangerous work. Dempsey stipulates that the army’s officer corps does not look like America: those in the senior ranks are “predominantly white and male and come[s] from a middle- to upper-middle-class background.” He fails to add that, in addition, there are no out-of-the-closet gays to be found among them. News reports about the academy in the born-again epicenter of Colorado Springs, suggest that the USAF officer corps is even less representative than the army’s. Obviously, absent a draft, there are limits to what the all-volunteer military can do to prevent this disconnect. But the issue at least suggests changing the policy for recruiting cadets to include a higher percentage of promotions from enlisted ranks, which are, in Dempsey’s words, “much more diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, and come from more modest socioeconomic backgrounds than officers.”

2) To what extent can we properly call the “military” — broadly construed to include those under active duty, plus military families, plus veterans, plus the communities that support and depend on their bases — an homogenous voting bloc in the Republican coalition? They are certainly disproportionately found in the Red States and their muscular deployment is certainly cited as evidence of the GOP’s national security credentials. Yet Dempsey’s work suggests (for enlisted soldiers at least, not the officer corps, not other branches of the services) that socioeconomic factors trump military identification as a determinant of political affiliation. Members of the military are disproportionately non-white, heterosexual, male, young, non-suburban compared with the population at large. Dempsey suggests that statements about their political ideology should only be made after controling for these demographic factors first.

I was a junior grade officer in the Army 1985 – 1991 (LT/CPT). When I look back on my experience, it strikes me as how “apolitical” my experience was. Sure, there were pictures of the “chain of command” all the way up to Reagan or Bush in every company orderly room, but that was about it for politics. Officers, even over beers, seemed to keep it to themselves.

Have things changed since?

this isn’t important at all

It is important. If the military’s political views don’t reflect those of America, then changes have to be made. It’s very dangerous for a country to build up a powerful military that has a skewed ideological bent.

I think that the politics of military officers (and perhaps to a lesser degree enlisted) has a biphasic pattern, one which is not that different from what is seen in the rest of employed society:

Young, unmarried enlisted and officers tend more toward liberal, but perhaps less so than a representative sample of men and women just out of school in the civilian world

Mid-career, married officers and enlisted with kids have characteristics that tend to correlate with being more conservative, so it’s not that surprising that officers and senior NCOs become more conservative as they more through their careers.

In the senior leadership, especially in the officer corps, there is a perception that promotion beyond Colonel (i.e. to Brigadier General and higher) is more reflective of connections/politics/personality and less so of merit than earlier promotions. I think it entirely possible that the sort of person drawn more to command and less to action (you often leave the field to put on your star) would be likely to trend left of center. Also, there is a tendency for the officers to reflect the regime in power. A Shinseki or a Clark might flourish under Clinton, whereas a Franks might be promoted more rapidly under Bush. These are of course broad generalizations, but they might explain the seemingly disproportionate number of left-leaning former generals in politics.

One thing to remember is how you judge whether you are a lib/con is by comparing yourself to those around you. When I was in the military I thought of myself as fairly in the center. Once I got out and moved to Minneapolis I found out I was a right wing nut.

Er, officers are politically conservative. Well, knock me over with a feather. My first day in ROTC, our instructor wrote

RHIP

in big letters on the board. Gotta have at least a BIT of conservative streak to accept that!

The same way, for example, one has to accept that college professors are more likely to be of liberal bent.

Skewed ideological bent? When an organization is made up of those who volunteer to be in it, it logically follows that the people in the organization feel strongly about the work that it dows. In the military, that currently is fairly conservative. In the educational system, that currently is fairly liberal.

To answer Robert’s question – I’ve been in 20 years now, from Private to Sergeant to Commissioned Officer. The military rarely discusses politics, just like any other citizen, in the workplace. It is socially unacceptable to bring religion or politics or any other sensitive subject up in the workplace. Just like any other group of working professionals. To answer Aaron’s issue – how is this a “skewed ideological bent”? This data seems to mirror other studies of white collar (officers) and blue collar (enlisted) americans. The military members are simply a group of americans – white collar/blue collar/white/black/latino/etc. No different than their fellow non-military citizens.

Very interesting in that it shows up the strange dichotomy between liberal/conservative bias by the pollsters. By thinking this is the breadth and sweep of American thought and feeling they ignore other sources of it. The majority of the military tends to adhere to Jacksonian principles, which are captured well neither by conservatism nor liberalism but by individualism and honoring the society by giving back to it by protecting it. While many try to lump these into a ‘conservative’ bin, they do not fit overly well due to the extremeness of personal liberty and not taking half-measures on things military nor trust in others save proven friends. And neither do they fit into the ‘liberal’ bin due to the social responsibility factor that appears to be missing from social liberalism for all its talk of culture.

So how does one view a suite of questions that leave out important things to the individual getting such a form? Represented by no party and neither side of liberal or conservative but something different not recognized. Not polled for it goes unmeasured… not thought about it goes unrecognized to those that wish to have easy bins to pigeonhole folks into.

And just who represents that one-third or so of the Nation that walked out on the two party system in the 1970’s?

And do their sons and daughters show up in the military? In what numbers? And why?

Something no pollster asks and so we shall never know… just who these people *are* and how they feel about the *rest* of the Nation.

“A permanent ideological and sociological disconnect between the republic and its military would pose perils for both.”

Considering that was the case for the military and the civilian government for most of their history up through WWII, I don’t see how this can be justified other than by fear based upon a lack of knowledge.

From Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian 1866-1891 by Robert M. Utley:

Chapter 4. The Army, Congress, and the People. “Sherman’s frontier regulars endured not only the physical isolation of service at remote border posts; increasingly in the postwar years they found themselves isolated in attitudes, interests, and spirit from other institutions of government and society and, indeed from the American people themselves…Reconstruction plunged the army into tempestuous partisan politics. The frontier service removed it largely from physical proximity to population and, except for an occasional Indian conflict, from public awareness and interest. Besides public and congressional indifference and even hostility, the army found its Indian attitudes and policies condemned and opposed by the civilian officials concerned with Indian affairs and by the nation’s humanitarian community.”

Don — Thanks for the history lesson. Are you implying that the treatment of the plains Indians by the army (not “humanitarian” Utley himself concedes) was exemplary social policy? Are you implying that the collapse of Reconstruction and the introduction of Jim Crow was a desirable development? If we are facing comparable catastrophes in the approaching decades then I, personally, would classify that as a peril for the republic. Regards –Andrew

1) To what extent is the military in general, and the officer corps in particular, unrepresentative of the population at large? A permanent ideological and sociological disconnect between the republic and its military would pose perils for both.

Failing some more details, I think you’re making a whole lot of stew from one oyster. The officer corps in particular is unrepresentative of the population in several ways automatically: median age, education (all military officers have at least a BA, senior officers commonly have postgraduate degrees), gender distribution (predominantly male), and at least in some ways, politically.

The notion that this would lead to a “Praetorian Guard” seems a bit of a stretch, though.

As a Chief Warrant Officer with two graduate degrees and the son of a career infantry officer, I think ‘ajacksonian’ hit the nail on the head. Libertarian is a better descriptor. Military officers are sent to foreign lands where govts are corrupt or failed. Individual freedom trumps government. I think Ms. Noonan has spent time with combat arms officers who seem to be less socially conservative. I liked the study but I think the survey was skewed to a bad model of left-right/liberal-conservative choices. Also, I would love to see the data breakdown among branches. MI is hugely liberal in my experience.

Charlie Colorado — you may be right, maybe just an oyster not much stew. I hope so. Your point restates the question I was trying to raise after reading Dempsey’s summary: namely, if all the differences between the military (officers or enlisted) and civilians can be accounted for by controling for demographics such as you cited, then there is no worry.

If, however, those factors of age, education, gender and so on do not account for any split there might be between military and civilian, that would imply that the all-volunteer military is self-selecting from a non-representative ideological minority. Taken to extremes, that phenomenon would be cause for concern.

Regards — Andrew

One would think that polls based on self-identification of subjective terms like “very conservative” or “liberal” would tend to moderate results. That said, the breakdown looked consistent with my military experience, both officer and enlisted, where officers and career enlisted tended to be more conservative, and junior enlisted tended to be more reflective of the general population at their age.

During a brief visit to Parris Island this past weekend after a thiry year absence, a couple of things struck me about today’s recruits. Compared to my contemporaries, they appeared:

1) Bigger

2) Stronger

3) Smarter

They were also, as a group, whiter. There were so few blacks, hispanics and asians that it struck me that minority kids either have more career options than thiry years ago, or schools aren’t producing men and women who can pass the basic military qualification tests.

If there is a significant difference between today’s miliary and that of the past, it may be reflective of a smaller pool of individuals who choose or qualify to serve.

Thomas hints at my take. By “career military” I would wager that Ms. Noonan is speaking of the Officer corps. That she does not find them markedly more conservative than others is, I think, a reflection of the company she keeps. I’m sure many other journalists would remark that that in their experience professional academics are no more liberal than others.

It might be interesting to futher break down the statistics and find out whether there is a difference in political beliefs between combat arms and non-combat arms officers and enlisted soldiers.

Andrew Tyndall, restated: “If, however, those factors of age, education, gender and so on do not account for any split there might be between [journalists] and civilians, that would imply that the [MSM] is self-selecting from a non-representative ideological minority. Taken to extremes, that phenomenon would be cause for concern.”

Skewed ideological bent? When an organization is made up of those who volunteer to be in it, it logically follows that the people in the organization feel strongly about the work that it dows. In the military, that currently is fairly conservative. In the educational system, that currently is fairly liberal.

Posted by: Nony Mouse | Jun 22, 2006 5:23:00 PM

—————————————

Nony Mouse, it’s ridiculous to compare the military with the educational system. The educational system isn’t going to take over the country by force. A military with an ideological agenda just might. That is a real possibility when the military is run by a bunch of right-wing extremists. What happens when the Republicans aren’t quite able to steal the next election? Will they use the military to retain power? That is my great fear, and it is why I do not support a volunteer military. If we absolutely must have a military in this country, then we should have a draft. That would prevent the military from becoming a dangerous political arm of the conservative movement.

Thomas raises a good point. When I am polled I really don’t know how to answer the left/right or liberal/conservative questions. There is more than one axis to most peoples political views.

I am a strong supporter of individual freedom which would make me liberal on social issues although I tend to be socially conservative in my personal life. I support a much smaller government, especially on the Federal level, which would make me fiscally conservative. However what is behind both of those is a belief in individual liberty and responsibility.

I followed a link to this post and I have not read the mystery pollster before so this question may have been answered here.

Has there been any serious effort to come up with a more or less standard way to poll peoples political positions? Given my frustration when I am polled I don’t trust the results much.

Aaron,

Get stuffed. The U.S. military eats, sleeps, and breathes the importance of maintaining civilian conrol over the armed forces. Take your meds and the voices will go away. I promise.

Aaron,

You are so insulated in tinfoil it isn’t funny. The US military, EVERY member, takes an oath to the CONSTITUTION, not a person or party. Your own disconnect from the military and personnel serving is frightening. We serve an ideal….that a more perfect union is possible but that evil exists and that there are people that wake up everyday wanting to destroy freedom. You might think that sounds cliche, but I (in Iraq, SA, Haiti, etc.) and my son (who was in Iraq) have seen it up close and personal. I wear the uniform so you can speak freely. Continue to speak because I know you can’t just say ‘thank you.’

Thomas that’s a crock and you know it. I could still speak just as freely without the military. Who would have taken us over in our lifetime? No one, that’s who. I have absolutely no reason to thank the military. But if you want to keep spouting that to inflate your own self-importance, go right ahead. The military is nothing but a massive drain on our treasury, and an implement of imperialism that turns the entire world against us. And sorry, I don’t believe that any organization that is skewed so ideologically as the military can say they don’t care about politics.

Aaron. Can you say conflating variables? One, I know our defense structure is a massive drain on the treasury. Two, we are an imperialist entity. However, we became that after WWII when it became apparent that Europe needed to be occupied and pacified. If you don’t believe a military is needed than you are an overly optimistic utopian. Pssst…here’s a secret, there are things that go bump in the night and one of those was the Soviet Union ‘during our lifetime’. Or are you a true leftist and believed in the benevolence of Uncle Joe? Whatever, your distrust of our own military shows everyone here who is paranoid and who is not.

To civilians, the military could come to seem like a Praetorian Guard. The military, in turn, could come to feel misunderstood and disrespected in its dangerous work.

Have the 60s, 70s, and early 80s already been forgotten?

Aaron, you want the military to have a less consertvative idealogiacal bent, fine. Let ROTC back onto campus at Harvard, etc. Liberals should stop disparageing the military and encourage their sons and daughters to join. On campus professors should do the same. Opening up ROTC onto more campus’s won’t militarize school, but it will liberalise the military.

Oh so the Aaron finally shows his true colors….

As far as a disconect Aaron, yes there is and this is why: as long as the military is an all-volunteer force it will always be a self-segregating institution. If libs don’t want to join, they don’t have to. But don’t be surprised if the military doesn’t have a ‘liberal’ bent if NONE OF THEM JOIN UP. And if they don’t join up, whose fault is that….? I blame parents who never instilled the sense of nation, duty or service beyond taking care of my own selfish needs. If you want to effect change, it’s far more effective to do it from within than to stand on the sidelines and bitch. A draft? A drafts purpose is to create numbers. Period. To use it as a political tactic will bring disaster.

Do I care about politics? Yeah, I do. But unlike some folks out there, the military doesn’t wear our affiliations on our sleeve. I don’t force feed my political agendas on my subordiantes or require them to have the same political bent that I do. That is a BIG no-no. There are no “Political Officers” in our military. That’s more than I can say about some other institutions in this country. I serve this nation, REGARDLESS of who is currently in office (and believe me I have like some president a whole lot less than others). I may not like it, but that is why we indoctrinate every single member of the importance of civilian control, loyaty to the NATION and being apolitical on the job. You seem to think everyone in uniform is an automaton mouthpiece of the right. Give me a friggin’ break and a little bit of credit.

As far as your belief on the validity of the military, well in a perfect world where everyone was shiny and happy, yeah there would be no reason for us to exist. But you know what, that perfect world has not existed since the Garden of Eden (or if you are the non-religious type, NEVER). The very reason why no one can hope to take us over to use strong arm tactics against us it that the US military will give them a smackdown if they ever try it. People don’t hate the US because of our military. They hate us because they are jealous of us or hate what we stand for. Simple as that. All the rest is just babble. People who think like you put would put us in a state of defenselessness because you don’t see any enemies out there. Well guess what, often times your enemies don’t manifest themsleves until they have buried a knife in your gut.

Throughout the history of America the military has been built up for war and then systematically gutted after the war is over. Those with experience were released from service and a very small military scrambled for crumbs to operate and train until needed again. Once America needed a strong military again, the rebuilding process was not only more costly than maintaining a well equipped professional military but valuable time was lost by implementing a draft and training civilians to be soldiers. The cost was not only economic, inexperienced soldiers were thrown into combat with inexperienced officers and the result was a butchers bill of deadly mistakes.

When the media focuses on the number of dead soldiers every time a nice round number is reached they fail to point out that a military at war for this long has never sustained this few casualties. The reason that our casualties are so low is because we do have a professional military that is well trained.

Look at the history of our armed forces at the beginning of any war up to and including Korea and you will see what inexperience and lack of training and equipment has cost in lives.

Look back in history and you will also see people like Aaron who didn’t see the need for maintaining a standing professional military. The saying that ‘those who do not know history are condemned to repeat it’ comes to mind.

Mark —

One of the difficulties with opinion research is that it doesn’t seem to do a good job of ascertaining the salience of the issues being studied. We ask respondents what they think of, say, abortion, but we don’t often learn how important an issue abortion is to them.

It may be that Peggy Noonan’s insight is correct despite the polling data, because it may be that social issues just aren’t very important to career military personnel. They may indeed report conservative views on these issues when asked, but those views may be qualitatively different from those of movement conservatives for whom social issues are the raison d’etre of their cause.

I’m very skeptical of survey research that focuses on a unique population, such as the military, without looking at how their unique experience might influence their opinions.

My 2 shekels.

Ron

Let me extend some of what armynurseboy said. Committed lefties tend not to join up. People who hate the military rarely join up. Not all those on the left hate the military, but those who hate the military are pretty much all on the left. Military folks can figure that out, since we’re drawn from the same society as everyone else. Why would we support politicians who hate us for being in the military? That alone brings many moderate officers into the Republican camp, I think. If you were a moderate-to-liberal Marine reservist in Murtha’s district, would you vote for him after he has slandered the Corps?

Some other points: A survey of the other services would yield slightly different results than the Army. Air Force officers would be (I think) even more conservative than Army, and AF enlisted might be more conservative as well.

Long-service enlisted men include more minorities than the general population, and probably more than the proportion of minority men in the general population. If they trend more conservative than young recruits, there’s something else going on than simple models of minority men tending to vote Democrat.

And, to throw my $0.02 where not needed, Aaron is both paranoid and poorly educated. He should read less Chomsky and less New York Times, and more… Heinlein?