The nearly final 3.6% margin by which Ned Lamont defeated Joe Lieberman in yesterday’s Connecticut Senate Primary (with 98% of precincts counted, Lamont leads 51.8% to 48.2%) was certainly closer than the margins on the final public polls. The two polls conducted last week by Quinnipiac and Research 2000 had Lamont ahead by six and ten percentage points respectively. An earlier survey by Quinnipiac had Lamont ahead by 13, and a mid-July survey by Rasmussen had Lamont ahead by 10.

The Quinnipiac pollsters will rightly point out that their final results fell within the 3.5% margin of error of their final poll, no small feat given the degree of difficulty in polling this unusual off-year primary election. But consider that the turnout of more than 282,000 voters or nearly 41% exceeded nearly everyone’s expectations and far surpassed the 25% historic average for primaries featuring a governor’s race. This leaves a few open questions, at least from my perspective:

- Did Lieberman narrow the gap in the campaign’s final ten days, as suggested but not quite confirmed by the last two Quinnipiac polls?

- Or was Lieberman consistently closer in Lamont’s rear view mirror during the final weeks than the public polls made it appear? Did the sampling methodologies and likely voter models of the public polls consistently exaggerate Lamont’s during the campaign’s final weeks?

It may be possible to answer some of these questions with the poll and vote return data, although we do not have access to all of the relevant data. For example, both campaigns conducted internal tracking polls that provide an independent assessment of the trend over the campaign’s final week. Do those surveys confirm a late Lieberman rebound, or was the second-to-last Quinnipiac survey, the one that showed Lamont ahead by 13 points, an outlier?

Campaigns are often willing to disclose internal data once the campaign has ended and the dust cleared. Unfortunately, since the Lieberman-Lamont contest continues, such a release from either camp appears unlikely.

The geographic turnout patterns are also relevant. Charles Franklin has already posted an amazingly thorough (and graphical) turnout analysis of the turnout showing that Lieberman did better in the larger towns and cities, while Lamont did better in less urban areas. He also confirms the so-called “Volvo/donut” turnout pattern suggested yesterday by Hotline On-Call, that turnout was higher in the smaller towns where Lamont had an advantage, lower in the larger towns where Lieberman did better (see also Hotline‘s follow-up analysis this morning).

This pattern leads to two questions: First, how well did the various polls do in modeling the geographic distribution of the vote? What portion of their completed likely voter samples came from the smaller towns where Lamont did better? How did that distribution compare to reality and did that distribution vary significantly from poll to poll?

Second — a question we can answer with data in the public domain — how much did the “Volvo/donut” geographic pattern depart from past history? Vote turnout is typically lower in more urban areas. The question here is whether the urban-rural turnout gap was bigger or smaller than in previous elections. If so, “likely voter” models based on past experience may have been off as well. Of course, if the smaller towns contributed a larger than expected share of the total vote, it would imply that a poll sample based on past turnout geography would understate Lamont’s vote, not overstate it.

It would be certainly be educational to try to answer some of these questions here, although most of the data we could use to try to answer these questions are in the hands of the pollsters.

PS: About that Exit Poll — CBS News has posted a brief report online. UPDATE: At 2:00 EST CBS posted a second more in-depth report that includes results ot all questions. The complete report has much to chew on including cross-tabs by demographics (age, race, education, religion, income, union membership and self-reported ideology). The most relevant finding to current speculation about an independent candidacy is as follows:

Most Democratic primary voters would not support an Independent run for U.S. Senate by Lieberman this fall, even though the majority said they approve of the way in which he is doing his job . . . .

If Lieberman does decide to run as an Independent against Lamont and Schlesinger in November, he may find that many Democratic voters will choose their party’s candidate instead of him. In a hypothetical three-way race against Lamont and Schlesinger, Lamont would earn 49% of the votes of these Democratic primary voters, and Lieberman would receive 36%.

Among Lieberman voters, three out of four say they will support Lieberman again under those circumstances; 16% are not sure, and 6% say they will vote for Lamont. Lamont retains more of his voters; 88% of them say they would vote for him in November.

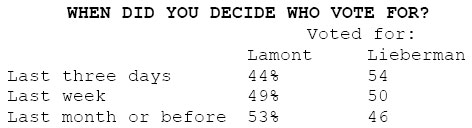

And oh yes — the reason political junkies love exit polls — the report also includes directly relevant to the central question I discussed above. The exit poll provides clear evidence that that Lieberman gained slightly over the last week of the campaign:

Three quarters of voters said they made their mind up about which candidate to support a while ago — in the last month or even earlier, and those voters went for Lamont. But the race appears to have tightened in the last few days, and Lieberman ran ahead of Lamont among the 16% of voters who made their mind up in the last three days.

[Click the table for a slightly bigger, less fuzzy version]

Such a late trend does make a certain amount of sense: A disproportionate share of the late deciding voters — probably including a lot of women, conservative/moderate Dems, etc. — flirted with the possibility of voting for Lamont but in the end came returned to what was (for them) a safer, more familiar choice.

Meet Joe Lieberman’s Worst Nightmare

Liberal bloggers jumped on Ned Lamont’s bandwagon before he even owned one. Now the anti-war crusade

Charles Franklin has already posted an amazingly thorough (and graphical) turnout analysis of the turnout showing that Lieberman did better in the larger towns and cities, while Lamont did better in less urban areas.

The link was not working.

very interesting. The note from the Courant:

Lamont rolled up lopsided margins in the Farmington Valley, Litchfield County, the lower Connecticut River Valley and scattered suburbs around the state. He won Hartford and Lieberman’s hometown of New Haven, which first elected Lieberman to the state Senate in 1970.

Lieberman dominated in the New Haven suburbs, the struggling rural towns of eastern Connecticut and old mill towns of the Naugatuck Valley, home of conservative Reagan Democrats and the place he chose to begin his campaign bus tour 10 days ago. He also took Bridgeport.

Lamont-Lieberman Exit Poll Results

Taegan Goddard has obtained the CBS/NYT exit poll results from the Lamont-Lieberman race. The results are somewhat surprising.

Overall, 78% disapproved of the decision to go to war in Iraq and, of those, 60% went for Lamont. Going in, Id have …

I’d look at the black turnout. Pollsters often miss it because somewhat by definition, black turnout organizers are paid to make election day actual turnout higher than the normal polling indicates. Also, it is a well-known desperation tactic of embattled incumbents to pour tons of money into their black turnout operations in order to close a late gap. Nowhere but in a Democratic Primary is the black vote more influential, and more volatile.

Link repaired – thanks Joe S!

I stumbled across your blog while I was doing some online research. One has to wonder how the night would have turned out if Independents had been allowed to vote–without being forced to declare a political affiliation they do not truly feel, that is.

It seems to me that while Lieberman may not retain all his primary votes, he will retain most of them (75%)plus a majority of the independents and Republicans. I believe that the independents who may be left leaning obviously have no loyalty to the Democrat Party, since they have not so registered, will vote heavily for the well known and now independent Lieberman

I think Lieberman did close the gap as Democratic voters such as blue collar workers, center-right dems, and women stuck to as you put it the safer, more familiar choice. I doubt that 13-point gap was just an outlier, because Ramussen did a poll when Quinnipiac showed at a 4 point advantage for Lamont and it showed Lieberman losing by 10. Also, an MD-based firm polled for a CT newspaper and they showed Lamont up 10.

I’d be interested to know whether the CBS exit poll tracked whether women were more or less likely to switch back to Lieberman at the last minute – I’ve read (and confirmed anecdotally) that women are much less likely to support the hard-line approach to war than are men. I’d expect that to offset the ‘safe choice’ option pthers have mentioned as an explanation for Lieberman closaing the gap.

Lieberman will win. I’ve just gotten back from a Connecticut vacation and polled several of my friends who live in North Branford, Naugatuck, New Haven, West Haven and Milford, 4 are registered independents and 5 are registered republicans. They are all voting for Lieberman.

I live in TN and planning to vote for Corker. I voted for Ed Bryant in the primary, but I have no choice, no way that I will vote for Ford.

MB-The last sentence of your post could easily be seen as condescending-perhaps as those women and others learned more about Lamont, they realized he is an empty suit. If they’d merely wanted a “safe, familiar choice”, they wouldn’t have strayed from Lieberman in the first place.

Other obvious questions… how much impact did the bogus “Lamont hacked my website” spin have on the election, and will it hurt Lieberman going forward? What about his lightning-quick abandonment of the Democratic party and subsequent independent candidacy? Or, for that matter, his obvious GOP support in this race?

Florida 22nd CD – New poll has Shaw (R) ahead

One of the key competitive House races in the country is Florida’s 22nd, held by incumbent Republican Rep. Clay Shaw for thirteen terms. Shaw is opposed by Democrat Ron Klein in one of the most expensive House contests of all…